It was the last meeting of my last course for my post-graduate studies. My professor required all students to do an oral presentation of the final research paper. I was done with my report when she proceeded with the inevitable cross examination, “What personal lessons did you learn when you did this research?”

My mind raced for an answer. The day before, I expected the professor would ask questions about the paper and planned templates for my answer.

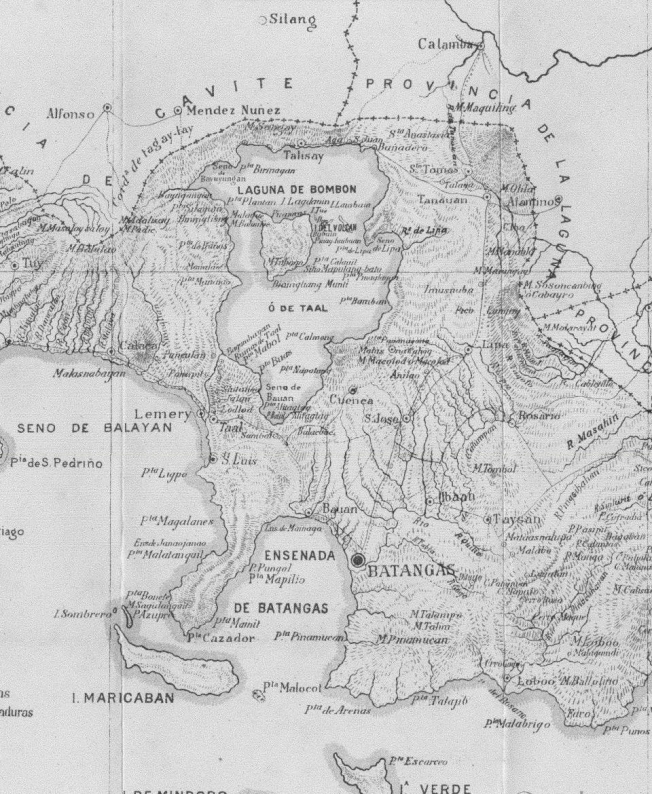

If the question is, “Why did you choose the topic?” My answer would be something like this: I was born and raised in the town of Cuenca in Batangas. We lived, as Filipino historians put it, bajo la campana (under the church bell). Our home is literally a stone’s throw away from the municipal high school, the municipal hospital and the church. I spent my childhood waking as early as four thirty in the morning since that is the time the church bell ringer plays the bells. Every day for almost ten years, I listen to their sound, wide awake but not rising until 5:00AM. It was during one of these early morning habits that I discovered the difference of the sounds played by the bells. I noticed that on some days, only one bell is played while on certain days, the sound is longer and all of the three bells of the Parish is played. I did not pay attention to all of these until I was choosing the topic for my final research paper.

If the question is, “What specific personal social activity can you associate with the bells of Cuenca?” This will be my answer: Besides of serving as a personal alarm clock, the church bells also reminded me of the Angelus, or as the people of Cuenca call it, ‘Orasyon’. At exactly six o’ clock, a single bass tone will reverberate from the bell tower as a signal for all Catholics to pause and pray. I will be finished when the bass tone is done playing and as the merry sound of the alto and tenor bells begin, I walk to any elders in my presence and kiss their hand. I will say, “Mano po.” They will place their right hand on my crown, saying, “Kaawaan ka ng Diyos at magbabait.” I also remember that on the day we buried my paternal grandfather, the bells tolled when the hearse entered and exited the church patio. The sound was slow and sorrowful. This is opposite of the sounds the bells played every Sunday. The melody is quick and cheerful as if inviting the faithful to rise very early in the morning to prepare for the mass. I remember hearing the same sound thirty minutes before each mass so I make it a point to go to the church once I hear the call for the second mass. Otherwise, I will end up standing for one hour.

If the question is, “Can you cite the significance of your research in an urban setting?” I will answer this: When we moved to Manila, I found the location of our home similar to the one we had in Cuenca. What was surprising was even if the church had a bell tower and a bell, I never heard the church bells ring very early in the morning. I had to buy an electronic alarm clock so I could wake up early for school. Thinking that I may have been sleeping too soundly, I decided to listen for the church bells at six in the evening. I heard the honking of the jeepneys, the whirr of the tricycles motors and the conversations of passersby. Without a signal for the Angelus, I eventually stopped praying it. Eventually, I also forgot to kiss the hands of my parents. On Sundays, I had to listen to the church amplifier to figure out if the mass is almost finished. Sometimes, the amplifier is overpowered by the sound of the jeepney motors that I had to go to the church myself to figure out if the mass is finished or not. Some days I guessed right, on other days I am so wrong that I end up attending almost two hours of mass.

I was not expecting the question the professor asked that I did not prepare for it. It did not help that when she announced the rubric for presentation, my answer will have the lion’s share of my final grade.

Had she asked what difficulties I encountered in writing the paper, my answer could have been immediate.

I began by scouring for archival sources, most are written in Spanish. Since I only knew basic Spanish and had no time to undergo intermediate Spanish language classes, I had to devise a methodology that will bring out the results of the research without relying too much on the documentary evidence. I decided that the best way to obtain data was to interview the town elders, preferably aged 70 and above to get a grasp on how the bells were played during the mid-20th century to the turn of the 21st century. I thought it would be easy to find respondents, being a former resident of the community. I was wrong.

Ever since we moved to Manila, I only knew two persons aged 70 and above who lived in Cuenca: my paternal grandmother and my maternal grandmother.

I told this problem to my paternal grandma who responded with, “Ay madali la-ang yaan. Ako,” then she started counting with her fingers, “Ang Nita, ang Pansang, ang Pita. Tapos isama mo na ang iyong Nanay Lydia. Ow, ilan ga ang kailangan mo?”

“Lima ho.”

“Ay ‘di ika’y nakakumpleto.”

Asking the questions was easy. Grasping the Batangeño Tagalog was hard. For almost twelve years, I lived in Manila where Tagalog is a mix of English and Filipino. I barely know some Batangeño words then yet I had to be conversant with it, otherwise, my respondents will sense that I am an outsider and this may limit the data they may reveal in their answers. At the middle of the interviews, there were times I had to let the respondents talk among themselves as I pause and think of the meaning certain words before proceeding with the next question.

“At sa amin naman, sa anim kong anak. Si Raymundo la-ang ang nababali ang tuhod kapag nakapagdasal ng Orasyon.”

“Bakin ho?”

“Walang naluhod kundi iyon, sa ama’t ina.”

“Ay ang luhod niyon ay naka-gay-on.”

“Tungong-tungo iyon.”

“Hanggang hindi nabebenditahan.”

“Ay bakin iyong iba ay hindi na nahili. Ay iyon e sadyang nakaluhod. Ay wala nang nahili duon.”

“Ngay-on ay ginagaling na iyong hahagipin ang kamay at magmamano. Magaling na iyon, maswerte ka pa.”

Not until I was transcribing the interviews did I realize that “nababali ang tuhod” means to kneel. “Bendita” means the child kissed the hand of the elders after praying the Angelus. “Nahili” is to be envied. “Ginagaling” is to be regarded as excellent.

After the interviews came the field research. My research adviser told me that any field researcher knows that there should be an image of the front page of any newspaper whenever a site is photographed for evidence of the ocular inspection. This is proof, he said, that the photo was not digitally altered nor was it downloaded from the Internet. At nine in the morning, I set out for the town market to look for newspapers.

Finding none, I asked a policeman who sat beside what appeared to be the newspaper stand, “Saan ga ho iyung nagtitinda ng diyaryo?”

“Nakow, ih wala na Ineng at ika’y tanghali na.”

Hopeless, I walked to a branded branch of a convenience store and asked the salesperson the same question.

I got the same reply.

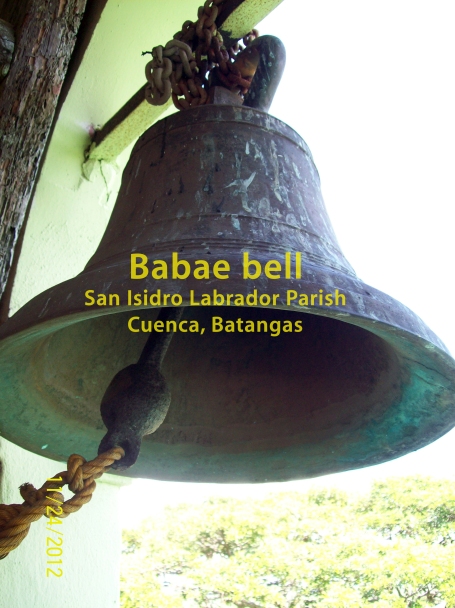

As I walked home, I thought of setting the camera with an automatic display of the time and date in every captured photo. Otherwise, the photos will be regarded useless for field research. The bells had to be personally photographed since according to historian Ricardo Trota Jose, there are details inscribed on the bells that tell its history.

My uncle was a lay minister of the Parish. He arranged my trip to see the bells which coincided with the Maintenance Chief’s inspection of the amplifier that is housed in the church bell tower. The Maintenance Chief climbed the steep stairs first while I followed. The staircase’s height was never an issue. What I feared then was that the staircase might break down any time since the wood creaked with my every step. This fear immediately disappeared when I reached the third floor of the bell tower. I was excited to see, hold and photograph the bells, taking note of the inscriptions on their waist and their chipped lips. I discovered that two of the three bells of the Parish were more than a century old. Two were casted from a famed bell foundry in Manila. The only bell I was not able to document was the biggest one, as it hung on a window by the staircase. Its location made it impossible for me to take pictures of its inscriptions that face the roof of the church.

My camera was filled with photographs by the time I descended the bell tower. By then I knew I only had one thing lacking for my research: a recording of the sound of the bells.

Documenting the sound of the bells was the most difficult part of the field research. I had to record the sounds heard before, during and after the bells are played. Since the bell ringer plays as early as four thirty in the morning, my uncle had to me wake half an hour early. Then we would go to the church bell tower to capture the highest audio quality. We repeated this routine several times when the bell ringer plays different sounds for different purposes.

My classmate gave me a signal that I had only two minutes left to present. I knew I had to speak.

“I’m a history major, Ma’am. I learned that when I wrote the history of the church bells of my hometown, I wrote the history of my people.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.