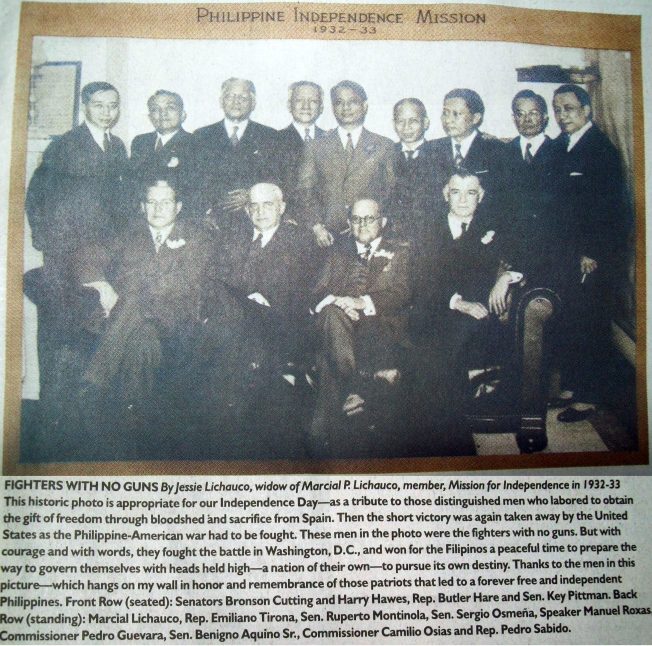

Photo from Philippine Daily inquirer, 10 June 2012, vol. 27 no. 182, p. A1

- The Political and Economic Situation in the Philippines (1931-1933)

The year 1932 saw Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (served 1932-1933) as the new Governor-General of the Philippines. Roosevelt, Jr. was the first to focus on the policies of the American administration in the Philippines on the social issues involving the little man. To solve these issues, he made it possible to delegate power to Filipino leaders. Problems plagued the Philippines and there were lots of efforts among Filipinos to solve these. The problem was there was less authority given to Filipinos and so they were not gaining any experience in governance. Ultimately, the problem goes unsolved and “every step forward in Filipinization was, broadly speaking, a step backward in the status of the lower classes, rural or urban.”[i]

The American community criticized the strategy of giving absolute trust to Filipino officials yet Roosevelt, Jr., delivered. During his short term as Governor-General, he was able to make a full economic turnaround.

First, he relieved landowners of land taxes, mindful that the small farmers might not have farms to tend in case these owners lose the land in the process of paying taxes. Then Roosevelt, Jr. sought the help of these landowners, who are usually the municipal or provincial leaders, in collecting taxes based on the amount they can pay. The condition was the local officials will constantly follow-up the payments, first the elites down to the poor.[ii]

Satisfying the upper classes, Roosevelt, Jr., then focused on the lower class, particularly the small farmers. He made it possible that farmers were knowledgeable in the agricultural science by conducting agricultural fairs in the public schools, assisting crop diversification, increasing rural credit in rural credit societies and rural banks and implementing a no loan contract, no loan made policy. [iii]

By the end of Governor-General Roosevelt, Jr.’s term of office, there was a balanced budget, reduced expenses and a surplus in a time of global economic crisis.[iv]

His only problem left was the Davaokuo or the slow Japanese penetration in Davao. Locals feared that there might be a Japanese political and economic takeover with their rising demographic. Moreover, as its leaders took up the responsibility of freeing Asians from the Whites and aimed to make Asia for Asians only, Japan began to build an empire and it seemed they are starting to makeDavao their stronghold.[v]

Aside from the younger Roosevelt, two other names reverberate during these years.

Manuel Quezon (1878-1943) is the Commonwealth’s Senate President who rose to power courtesy of his powerful oratory and his charismatic statements towards a full, immediate and complete independence.

Quezon’s rival was Sergio Osmeña, Sr. (1878-1979), Senate President Pro-tempore, former Speaker of the Philippine Assembly, the third highest-ranking Filipino before there was a bicameral legislature. Osmeña yielded his personal ambitions for the unity of the Nacionalista Party in two instances: first in 1922 on the issue of unipersonal versus collective leadership over Quezon; then in 1933 when the Nacionalista Party split over the acceptance of the first independence bill.[vi]

In both occasions, Osmeña and Quezon clashed over issues.

It was no surprise therefore that in 1932, when there was a revival of Filipino nationalism and there was a louder clamor for independence, Quezon sent the ninth Philippine Independence Commission for Washington without exact directions. This mission, more popularly known as OsRox—the name derived from the surnames of its leaders, Sergio Osmeña and Manuel Roxas—received only a fair warning from Quezon before they departed: the Americans may place their domestic concerns over the Philippine question. [vii]

- In the United States of America (1931-1933)

Quezon had reasons to say such things: the world was experiencing an economic crisis known as the Great Depression, a period of the worst depression in the economic history of America. The stock market crashed, “factories cut down production and laid off workers.”[viii] There was high unemployment, closed businesses and a lot of unpaid loans. American investors had to keep themselves in business so they withdrew their money in European banks. This action made the American problem a European one. International trade declined and American firms decided to cut-down production more and lay-off more workers. [ix]

However negative the situation maybe for the OsRox Mission, Quezon’s warning may be viewed on a different light. As Americans focused on the Great Depression, there might be an American majority who would want to dispose the Philippines. The American farmers viewed Philippine imports as competition. The same goes for the American unemployed who view the Filipino immigrant as a competitor in a very narrow job market.[x] Who wants a colony in a time of domestic financial issues? Better to keep the money at home than let it flow out.

- The struggle for the First Independence Bill

The OsRox Mission believed that the Great Depression may help their cause. Despite massive opposition from the American press, those in the houses of Congress want to hand independence to the Philippines, but not without conditions. The Mission’s original aim was to gain early independence yet after committee hearings, the American Congress now wanted to set a transition period of at least two and a half decades so that the Philippines will reach political, economic and cultural maturity. Further, they wanted the Philippine Legislature to:

- “limit production of Philippine sugar”;

- “restrict Filipino immigration to America”; and

- “balance Philippine-American trade benefits by a revision of the Philippine tariff”. [xi]

The American Congress immediately went to action. Senators Harry Hawes (1869- 1947) and Bronson Cutting (1888 –1935) created their version of the independence legislation, S.2743. At the House of Representatives, Butler Hare (1875-1967) introduced H.R. 7233 as its companion bill a day after. The Hare bill reflected what the American Congress wanted: a period of transition and a plebiscite to decide on an independent or autonomous status for the political side and a gradual increasing tariff in Philippine-American trade for the economic side.[xii]

By now, the OsRox Mission departed from their original aim of complete and immediate independence. This was impractical and impossible, according to the Committee hearings during the enactment of the bill. They had to make do of what the Americans are offering since it is better than nothing. When the House Committee asked the Philippine Mission to revise some parts of the bill, they came up with the following:[xiii]

- A five year transition before the granting of independence;

- An exact quota of Filipino immigrants;

- Honoring current trade agreements except for those involving the following products: raw and refined sugar, sugar, coconut oil and cordage (abaca).

Despite the quantity limitations for certain Philippine products, the bill still faced the wrath of the American farmers who wanted to impose drastic measures on what is already a strong, protectionist American economic policy. This was not surprising as American farmers viewed Philippine products as fierce competitor in a time of Great Depression. Nevertheless, this is the same group who favor immediate Philippine independence.

However, the concurrence of one bloc does not mean the concurrence of all parties concerned. American legislators still believed that with the impeding political chaos in Asia courtesy of the Manchurian Incident in 1931 and the political, economic and social immaturity of the Philippines, independence is out of the question.[xiv]

On 10 March 1932, the House Committee introduced the specifications of the Hare Bill:[xv]

- a limit of 800,000 tons and 40,000 tons for raw and refined sugar, respectively;

- a limit of 5 million pounds for abaca;

- a limit of 300,000 tons for coconut oil;

- a limit of 50 Filipino immigrants; and

- selling or leasing Philippine land for “coaling or naval stations”.

This was still not the final version of the Hare Bill. The final one lowered the quota of coconut oil by a hundred thousand while that of abaca’s lowered by two million. The period of transition increased to eight years and the “yearly reduction in import quantities was eliminated.”[xvi] Further, Hawaii was excluded from the immigration clause.

Republicans were against the Hare Bill but this did not stop the Democrats from drafting and finalizing the Hawes-Cutting Bill. The latter is in essence of the former. They differ in one thing: the date of independence. The Senate did not want to give a fixed date since there is uncertainty in Southeast Asia and there is still an economic depression. No one knows what the future might bring. America did not want to let go of the Philippines in a time of chaos so why place a specific date?

And so, on 1 March 1932, the amended and final version of the Hawes-Cutting Bill contained the following, subject to the acceptance of the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives:[xvii]

- Free trade for ten years, with quota on coconut oil, sugar and cordage that will exceed the limit;

- “A progressive export tax on Philippine imports after the first ten years” then gradually increasing at the rate of 5%, annually;

- Framing and adopting a Philippine Constitution and after ten years of implementation, a plebiscite on the independence question;

- A maximum annual quota of 100 Filipino immigrants to America; and

- The permit for America to retain and operate military and naval bases.

By April 1932, the combined versions of the Bills went into the Senate calendar for debate as Hare-Hawes-Cutting (HHC) Bill. To avoid further delays on the bill’s enactment, the OsRox Mission together with Senator Hawes contacted Ambassador William Cameron Forbes (1870-1959) to strengthen the weak point of the bill that is, the powers of America during the period of transition. Sen. Hawes consulted Osmeña and had the HHC amended according to Forbes’ recommendations:[xviii]

- The President of the United States can interfere with “fiscal and international” matters involving the Philippines;

- The American High Commissioner shall have “additional functions”; and

- There shall be an office for Financial Control whose main duty is to “duplicate copies of the Insular Auditor’s reports and hear appeals from the Auditor’s decision”.

These did not sit well with Quezon and the OsRox Mission yet Sen. Hawes added them anyway.

It will be almost two months before the HHC was finally called for debate. That time was enough for the political climate to change. Several senators were determined to block the bill by filibustering or by not attending the sessions set for debate. Other times, the bill is sent for committee amendments before it was scheduled for another debate then it was sent to the committee again.

By the time the Senate adjourned for recess on December 1932, the OsRox Mission faced the reality of that change in political climate. There was a united front to defeat the Independence Bill and the American press led the way. The New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, Washington Post and several dailies published reports that the Filipinos were “no longer in favor of independence and were not in sympathy with the stand and activities of the Mission in Washington.”[xix] The only counter attack the Independence Mission can muster was to publish “official statements, letters and circulars” to newspaper editors. Their efforts eventually gained ground. The Senate finally passed the HHC on the same month.

Among the finishing touches of the HHC were the Forbes amendments and the Filipino Chief Executive’s use of Malacañang Palace.

President Herbert Hoover (served 1929-1933) vetoed the bill the following year, 13 January 1933, stating the undeveloped political institutions and the still dependent economy of the Philippines. He added that the unstable balance of power in Southeast Asia also posed a threat in an otherwise young democracy.[xx]

“Immediately after the receipt of the veto message, the House started debate on whether to override the veto. After an hour’s debate, the House” overrode the President’s veto. The Senate soon followed. “On 17 January 1933, Hare-Hawes-Cutting Bill became law.”[xxi]

- Quezon versus the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act

Manuel Quezon was not pleased when Senators Osmeña and Roxas came home with the first Philippine Independence Bill. The clauses on Filipino autonomy, tariff limitations and military bases did not suit Quezon’s belief on full, non-negotiable and unequivocal independence.

The OsRox Mission argued that the economic events in America were perfect for the independence legislation for it was, undeniably, a step towards independence. They also feared that rejecting the HHC act will bring a message to America that Filipino leaders do not actually want independence.[xxii]

The disagreement caused the battle of newspaper chains in Philippine politics.

Quezon’s leadership in the Senate was threatened when the Tribune-Vanguardia Taliba (TVT) sided with those in favor of the HHC. It did not help that Carlos P. Romulo was their publicist. Romulo and the Pros gained momentum when these newspapers published the OsRox Mission’s successes at Washington. Quezon looked like the villain since he knew through experience that whoever took home the Independence Bill has the greatest chance of being elected as the highest official in the land should America grant the founding of a Commonwealth government.

The Antis launched a counter attack that displayed Quezon’s mastery of politics of manipulation and alliances. First, the Antis appealed to Filipino patriotism when they said that the HHC was for the American landowners’ benefit since they wanted cheap labor. Second, Quezon as the Nacionalista Party leader threatened a party split. Third, he recruited Romulo from the Pros.[xxiii]

Quezon wanted some changes in the HHC yet no one seemed to listen to him when he went to Washington on 25 April 1933.[xxiv] Congress made it clear that they together with their new President, Franklin Roosevelt (served 1933-1945), will “not act further on Philippine independence.”[xxv] Quezon got what he wanted, alright, but he wanted more. This did not sit well with the Americans who devoted so much time for debates on the Philippine question. That was when Quezon decided to throw away the HHC and with it, the OsRox Mission.

It will be almost two months before the battle between Quezon and Osmeña reaches the public. Osmeña raised the question of conducting a plebiscite to know the voice of the people regarding the acceptance or rejection of the HHC. Quezon had no choice but to accept. Otherwise, he will look antidemocratic.[xxvi] Osmeña thought the plebiscite will settle his quandary with Quezon. He was wrong. Quezon manipulated not only the Senate but his network of alliances to rally with him in rejecting the HHC.

First, Quezon had the funds of the remaining members of the OsRox Mission cut-off. To divert the public’s contribution to their fund and not the OsRox’s, Quezon appealed for funds to support “independence”. He also had the OsRox supporters voted out of their respective offices and replaced them with his allies. Then Quezon gathered together the “ultra-nationalists” such as General Aguinaldo, Ricarte, Bishop Aglipay and the Communists for his cause.[xxvii]

Quezon knew that there must be unity on the Philippine front so he resorted to some not-so-good tactics to reach his goal. His opponents viewed this as one-man rule. Quezon calls this by another name: patriotism.

- Quezon secures the Philippine Independence Bill

In the end, Quezon won the clash of the scribes men. His victory, however, did not mean that American legislators would be on his side. Quezon returned to Washington anew and submitted amendments to the HHC Act. Yet American leaders retained their “Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act now or nothing for a while” sentiment.[xxviii] Two months will pass and Quezon, determined to bring home the bill of independence, met with Senator Millard Tydings to discuss the possibility of finding a “common meeting ground” of Congress and Quezon and the Osmeña-Quezon factions. By February 1933, Representative John McDuffie joined the discussion. The group decided to revive the HHC Act and amend the military bases clause so that these are subject to negotiations two years after the independence.[xxix] The new bill will contain the HHC Act in essence; changes are purely for cosmetics.

President Roosevelt signed the Tydings-McDuffie Act on 24 March 1933. Almost a month after, Governor Frank Murphy called the Philippine Legislature for a special session to consider the Tydings-McDuffie Act. On 1 May 1933, the Philippine Legislature unanimously accepted it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Churchill, Bernardita Reyes. The Philippine Independence Missions to the United States 1919-1934, Manila: National Historical Institute, 1983.

Gleeck, Jr., Lewis E.. General History of the Philippines Part V Vol. I The American Half Century (1898-1946). Quezon City: R. P. Garcia Publishing, Co., 1984.

Hornedo, Florentino H., Ideas and Ideals Essays in Filipino Cognitive History.( Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House), 2001.

Perry, Marvin, A History of the World Revised Edition, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1989).

Encyclopedia

Philippine Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 1993 ed., s.v. “Osmeña, Sr., Sergio (1878-19?)”

[i] Lewis E. Gleeck, Jr. General History of the Philippines Part V Vol. I The American Half Century (1898-1946). Quezon City: R. P. Garcia Publishing, Co., 1984, p. 312

[ii] Ibid., p. 316

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Gleeck, Op. cit., p. 313

[v] Gleeck,Op. cit., p. 320

[vi] Philippine Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 1993 ed., s.v. “Osmeña, Sr., Sergio (1878-19?)”

[vii] Bernardita Reyes Churchill. The Philippine Independence Missions to the United States 1919-1934, Manila: National Historical Institute, 1983, p. 263.

[viii] Perry, Op. cit., p. 686.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 265

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 266

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 267

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 269

[xvii] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 271

[xviii] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 272

[xix] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 273

[xx] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 277

[xxi] Churchill, Op. cit., p. 278

[xxii] Gleeck, Op. cit., p. 322

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Gleeck, Op. cit., p. 323

[xxv] Churchill. Op. cit., p. 287

[xxvi] Gleeck, Op. cit., p. 324

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Churchill. Op. cit., p. 291

[xxix] Churchill. Op. cit., p. 292

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.